Confusion about the Electoral College

The United States of America is not a democracy. It is a representative republic.

By Ken Wackes January 2017

Few things are more confusing to students (and to many teachers!) than the Electoral College. “How can it be that Hillary Clinton is not our new president? She received 3 million more votes than did Donald Trump,” exclaimed eighth grader Hector Rojas in Miami. “I’m not really certain myself,” said his teacher. “Let’s research it.” “My dad said some college made the decision,” added classmate Evelyn Cordova.

Hector, Evelyn and their teacher are not alone in attempting to understand the election process. A street poll conducted among Christmas shoppers by a major news agency could not find one person who could explain how the Electoral College system works.

Here is an abbreviated explanation.

The United States of America is not a democracy. It is a representative republic. The Pledge of Allegiance includes the phrase: “and to the republic for which it stands.” The Constitution itself declares that “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government” (Article IV, Section 4).

In a democracy everyone gets to vote on everything. In a representative republic the people choose representatives who, in turn, make policy decisions on their behalf.

At the state and local levels the people vote directly for those they wish to govern and represent them (governor, state senators, state house members, mayor, county commissioners, etc.). On the federal level the people vote directly for U.S. senators and members of the House of Representatives. The election of the president and vice-president, however, is a task assigned to the states and not directly to the people.

- The election is carried out by electors.

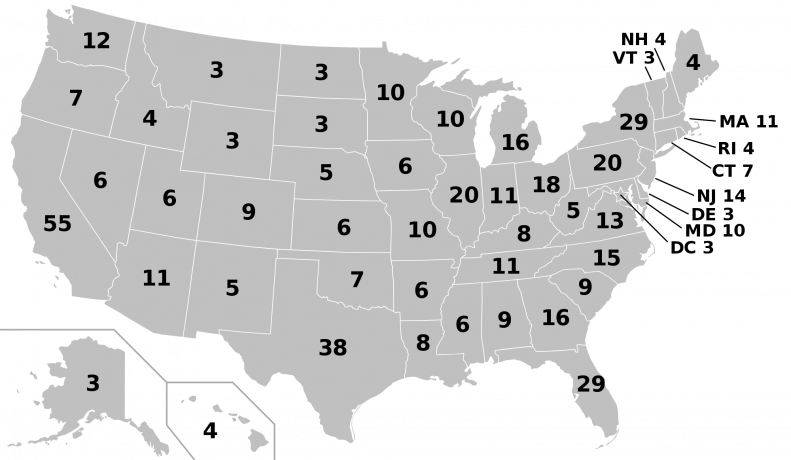

- Each state receives a minimum of three electors, one each for their two Senators and one for their member in the House of representatives, regardless of population. Additional electors are granted based upon the number of seats a state has in the House of Representatives.

- State legislatures may select electors in any manner that they choose. In most states Democrats select a slate of Electors and the Republicans do the same prior to the national election. If the Democrats’ candidate wins the state’s popular vote, their slate of electors cast their votes for that candidate. Likewise the Republicans if their candidate wins the state’s popular vote.

- Each state except Maine and Nebraska currently uses a “winner-take-all” system, whereby the presidential candidate winning the state’s popular vote is awarded the state’s entire slate of electors.

- It is at this point that the votes cast by the people in each state are important. If their candidate of choice receives the largest number of votes in the state, all of the electors appointed by the state are committed to vote for that candidate.

- The 538 electors assemble, usually in their state capitols, on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December.

- On this day, the electors cast the votes that officially determine who will be the next President of the United States.

- Congress meets in joint session to count these votes on the following January 6th.

To be elected President, a candidate must receive a majority (270) of the states’ 538 electoral votes. He or she does not need a majority of the national direct popular vote cast on Election Day.

In the recent presidential election in Florida, Donald Trump received 49.1% of the vote and Hillary Clinton 47.8%. Trump received all of Florida’s 29 electoral votes.

Although Clinton received 48.20% of the national vote and Trump 46.10%, Trump won 308 electoral college votes and Clinton 232.

A major factor impacting the 2016 electoral college vote was Trump’s receiving the majority of popular votes in 24 states and Clinton 14. Third party candidates prevented either Trump or Clinton receiving a majority vote in 13 states.